by Luke Henderson, University of Sydney

I adopted my first greyhound while living in New Zealand in 2015. Bob was a four-year-old ex-racer with a heap of personality and zest for life.

Though I didn’t know it at the time, in Australia, an ABC exposé was drawing widespread attention to the industry’s welfare issues. The documentary wasn’t making a big splash across the ditch, and I had very much bought into the “they love to run” mindset that endures in the racing world.

Over the coming months, I looked to learn as much as possible about Bob’s racing career and this incredible breed of dog more generally. I came across the exposé and began to unravel the extent to which the greyhound racing industry was not meaningfully held to account on welfare issues.

A ban on the industry was announced in NSW in 2016 following a special commission of inquiry led by The Hon Michael McHugh AC QC. The industry was deemed beyond repair, which seemed to be a logical conclusion.

The ban and the backflip

When the then NSW Premier Mike Baird “backflipped” on the ban, I and many others began questioning how and why this could be. These questions followed me closely over the next few years until I moved to Sydney and was presented with an opportunity to assess regulatory efforts in NSW since the backflip as part of a research dissertation for a Public Policy Master’s degree.

I was driven by the desire to unpack how and why animal welfare, the very reason a ban was sought, had been so swiftly decentralised from subsequent policy initiatives. The scope of my research looked explicitly to the concept of policy success, giving great focus to a framework that assesses which stakeholder policy decisions are serving. Across programmatic, policy-making, and political realms, what can be seen is that since the backflip, welfare has been decentralised from initiatives to the benefit of racing as the status quo.

Illustrations of this are many. Glaring examples include:

- Disciplinary action for wrongdoing demonstrating no capacity to curtail offences

- kennel inspections that have significantly reduced under COVID restrictions despite racing being permitted to continue concurrently, and

- a stark avoidance of the industry to bring in six-dog racing and straight courses even though industry commissioned research insists they are far safer than the traditional eight-dog races and curved tracks.

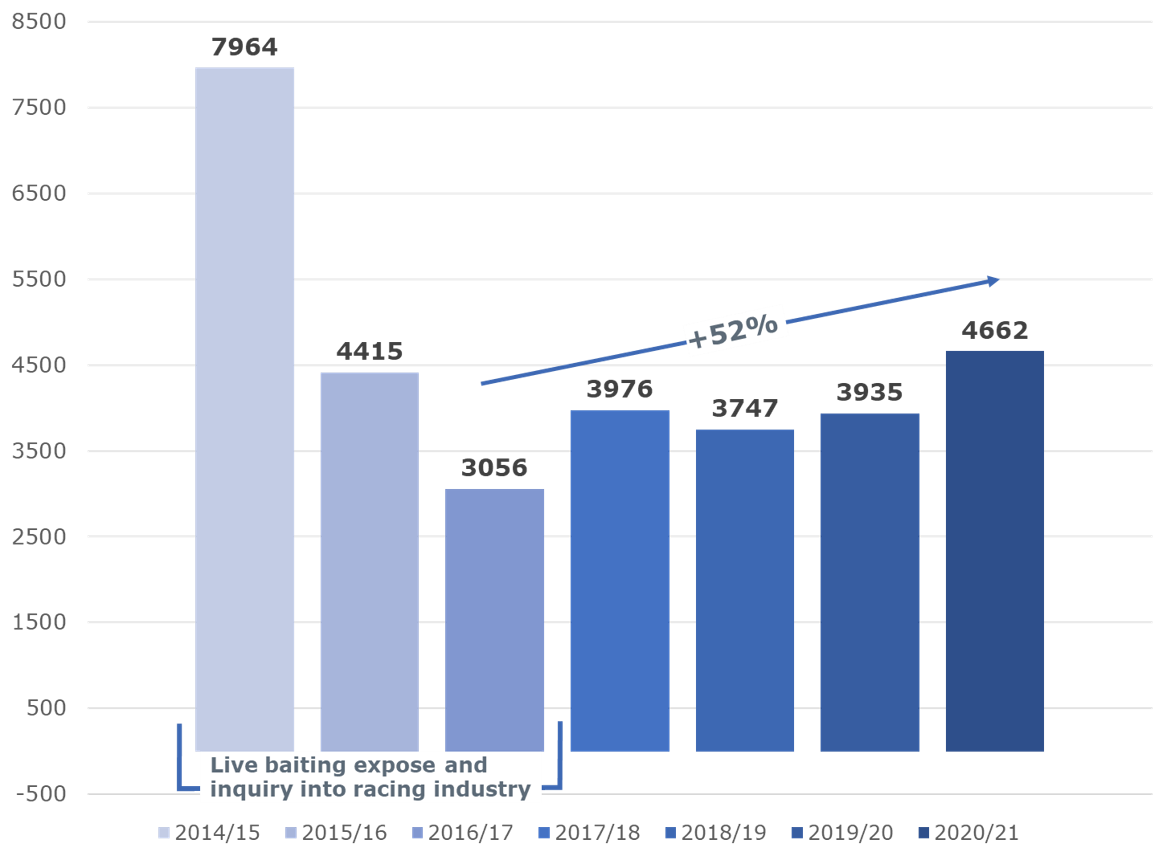

Even the number of pups whelped, which had initially seen improvement in the year following the exposé, is now seeing consistent increase year on year, feeding into the struggle faced by rehoming agencies that receive no

government funding.

Chart produced by CPG based on Greyhound Welfare and Integrity Commission breeding and whelping data

Five critical recommendations

My ultimate hope for the future is that greyhound racing is banned not only here in NSW but throughout Australia and the few holdout nations where it remains worldwide. Though participation and interest in the industry are certainly falling throughout Australia, it must be recognised that it is still deeply entrenched in Australia’s culture alongside a proclivity for gambling, so an outright ban may take time.

As we wait, my short-term wish is that the NSW Government and GWIC begin to make more meaningful improvements for the sake of racing hounds.

Gone to the Dogs? A case study evaluation of contemporary greyhound racing regulation in New South Wales

My paper makes five critical recommendations that should be considered:

-

-

- Transparent targets. Welfare trends are difficult to capture without quantifiable targets, which could be carried out under a Key Performance Indicator (KPI) approach. If they were introduced, policy design could allow resources to be directed where required to ensure continued improvement.

- Bridging the enforcement gap. Though more effective regulations have been introduced recently, offences remain stubbornly consistent, suggesting actions aren’t working. As a result, more agencies for compliance and enforcement within the industry must be considered.

- Funding and support for rehoming agencies. NSW Government funding for the industry has increased significantly recently, yet strains on rehoming agencies remain prominent. If funding for the sector from government is to continue, the needs of such agencies must be assessed alongside it.

- Public input. For public confidence in the industry to be maintained, it must first be transparent. Through periodic reviews, the saliency of animal welfare issues in Australia is poor despite general attitudes toward animal harm being one of condemnation. Public members, including those without connection to the industry, should be routinely included in future consultations on industry conduct.

- Comparative lens with other nations. How NSW compares with other states and Australia with other countries should be considered. Australia’s positioning as having the most significant greyhound racing industry in the world, and one of only a few nations where racing occurs, provides context that suggests long-term survival is dubious. Decision-makers should closely examine how greyhound racing is regulated in other contexts through benchmarking efforts.

-

For animal welfare advocates, I have two pieces of advice.

Firstly, be loud.

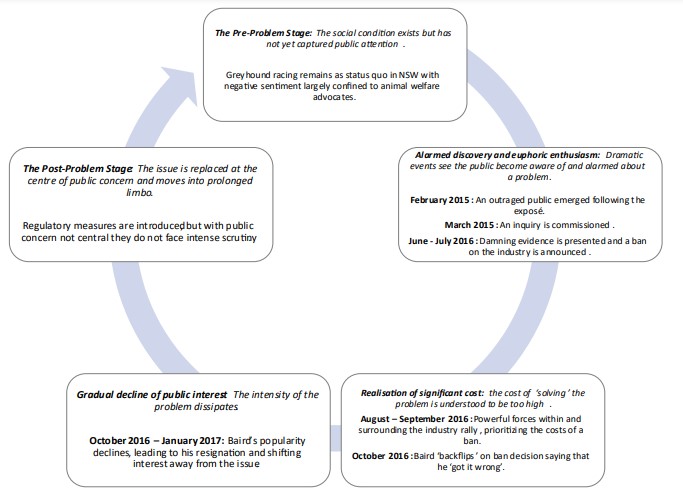

Peter Chen writes of a “significant modern defence of the status quo” in Australia’s politics of animal welfare issues. This resonates entirely in the NSW greyhound racing timeline of events, where the subject has moved out of public scrutiny and into a prolonged limbo (see Issue Attention Cycle).

Speaking up about these shortcomings can raise awareness among everyday Australians who may not know about the harmful systems. Only through speaking up can changes for the better begin to filter through. Follow the CPG’s lead!

Secondly, if you are in a position to do so, donate to or volunteer at rehoming agencies, or consider bringing a greyhound into your home.

Unfortunately, my first greyhound Bob passed away in 2020 after a short and frankly horrible battle with osteosarcoma, but the positive impact he had on my life was so powerful that last year I ended up adopting my second greyhound, the incredibly affectionate Cher.

Greyhounds are beautiful, unique and resilient creatures that will change your life, and I wholeheartedly endorse the breed as the ideal pet. Admittedly, I may be a little biased.