by a CPG volunteer

In case you missed it, CPG recently released a report on the state of greyhound racing in Tasmania and the findings unsurprisingly reveal a woeful state of affairs in terms of both integrity and welfare.

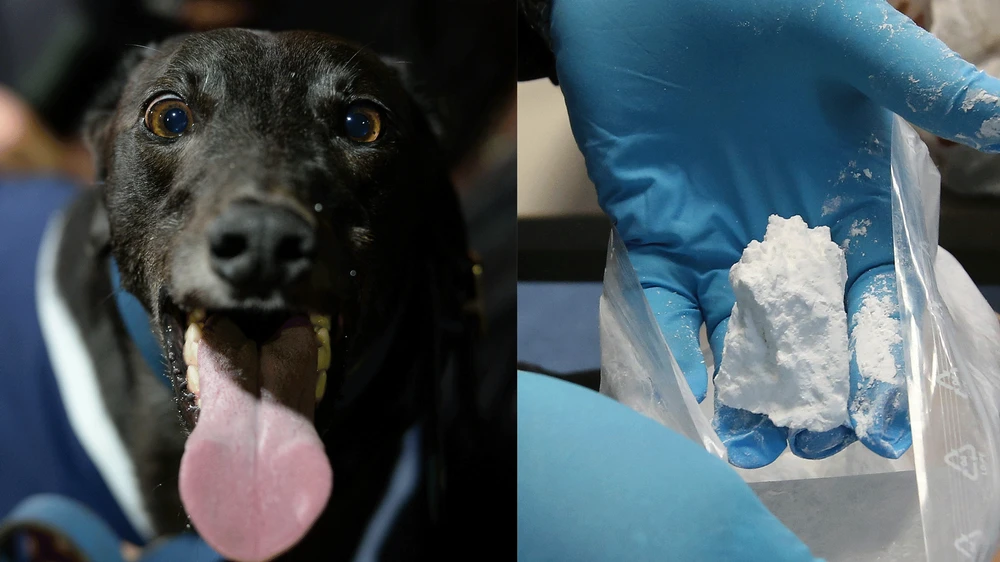

CPG’s report reveals a shockingly lax approach to anti-doping across all three codes of racing covered by the Office of Racing Integrity (ORI), the government regulator responsible for greyhound, thoroughbred and harness racing across the state. According to annual reporting on ORI’s performance not only is there no distinction between swabs taken in-competition and out-of-competition, but it also does not report on the number of samples taken within individual codes of racing. Instead, their reporting displays the collective data for swabs taken from horses, hounds, and even humans.

The absence of clear data indicates a serious lack of oversight with regard to doping controls in Tasmania, and leaves punters with little sense that they are betting on a level playing field. If ORI are relying solely on in-competition samples, we can be sure the detected doping reported is a gross underestimation of the real doping rate.

If the greyhound racing industry wants to be seen as ‘just like any other sport’, it needs to start behaving like one by implementing and adhering to adequate systems that demonstrate a genuine commitment to integrity.

Make it up as we go: penalty determinations lack meaningful framework

Unlike some jurisdictions, Tasmania does not have clear guidance for applying penalties when offences are being considered. Instead, stewards often provide vague references to comparable cases in Tasmania and other jurisdictions. This indicates a flawed system that favours a lowest-common-denominator approach, rather than one of consistency or best practice.

Steward decision reports also reveal peculiar considerations to justify lesser penalties. For example, in several instances the fact that a prohibited substance did not appear to improve race performance was factored into the penalty decision. In another case, the apparent high-quality upkeep of a treatment log worked in favour of a trainer administering treatment to a dog using a prescription only drug, despite not having a prescription for the drug, nor instructions on how to administer the drug. This is the equivalent of breaking the law, but at least keeping a record of when and how you were doing it.

Greyhound welfare standards out of step with animal welfare legislation

In recent months, there have been shocking revelations about sub-standard kennelling conditions at multiple sites across Tasmania, as well as evidence of the persistence of banned baiting practices. While the industry and its supporters always say that it’s just ‘a few bad apples’ when such stories arise, CPG’s report shows the problem is a systemic one.

According to key industry documents relating to standards of welfare, greyhounds are not entitled to the same basic levels of care that other dog breeds enjoy. But this does not come as a surprise, unfortunately, given the documents in question are owned by Tasracing (the corporate entity with a vested interest in the profitability of greyhound racing).

For example, the Tasmanian Government Animal Welfare Guidelines for Dogs – approved under the Animal Welfare Act – says dogs “must have the opportunity to exercise for a total of at least 60 minutes each day.” According to Tasracing’s standards however, the minimum expected exercise for greyhounds is a mere 10 minutes twice a day. In an effort to justify these lesser conditions, Tasracing has explained that greyhounds differ markedly from working dogs and “mainly eat and rest.” However, when convenient, Tasracing also claims greyhounds are elite athletes. Clearly the contradiction is lost on them.

Necessary interventions for a sub-par system

CPG’s report offers 13 recommendations for the Tasmanian Government and racing industry regulators to bring the state of greyhound racing into Tasmania up to minimum acceptable standards. These include a vastly improved doping control program, mandated penalties for those breaching the rules, and bringing welfare standards for greyhounds into line with the Tasmanian Government’s own Animal Welfare Guidelines for Dogs.

After all, is it too much to ask that if greyhounds are expected to be elite athletes on race day, they at least enjoy the minimum standards of care extended to any other breed the rest of the time? For the Tasmanian racing industry, apparently it is.

Image source: Vice Media Group: Doped Up dogs: Why Greyhounds Are Being Given Cocaine