Greyhound Racing New South Wales (GRNSW) has proposed a new local rule to reduce the unnecessary euthanasia of greyhounds by making it compulsory for all owners to attempt to rehome their retired greyhounds. Sounds good, doesn’t it? Unfortunately, whether this rule is sincerely well-intentioned (but badly thought-out) or nothing but lip service, it totally misses the point.

What is Proposed Local Rule 106A (LR106A)?

Proposed LR106A is described by GRNSW as an effort to keep welfare at the centre of the so-called ‘sport’ that is greyhound racing. Its aim is to “reduce the euthanasia rates of healthy greyhounds and promote responsible ownership” by making it mandatory for the owners for racing greyhounds to attempt to rehome their dogs upon retirement.

Here’s a summary of what LR106A prescribes:

Owners will only be allowed to have healthy greyhounds euthanased where it is undertaken by a veterinary surgeon and where an owner can demonstrate they have made reasonable efforts to have the greyhound rehomed.

Similarly, owners will only be allowed to surrender a greyhound to a local council where an owner can demonstrate that they have made reasonable efforts to rehome the greyhound .

- For the purposes of this Rule:

(a) a greyhound is considered “unable to be rehomed” if:

(i) the owner of the greyhound does not believe that the greyhound can be reasonably retained as a pet by the owner and the owner is able to explain why this is not possible in the relevant circumstances; and

(ii) a person has contacted the GRNSW Greyhounds As Pets program and at least two other rehoming providers who have declined to accept the greyhound for rehoming; or

(iii) a veterinary surgeon or rehoming provider has assessed the greyhound as not suitable for rehoming.

You can read the full description of LR106A here and the actual clauses of LR106A here.

Why LR106A Won’t Work

Whether this local rule was proposed with good intentions or just to make GRNSW look like they were doing something for greyhound welfare, it makes little difference to discarded greyhounds in danger.

Clause (1)(a)(i) seems pointless because even if many industry participants start keeping their retired racers as pets, after retaining a certain number of dogs they will no longer be able to keep every dog that passes through their hands while giving each one a sufficiently high quality of life and level of care. However, is this an acceptable reason to obtain and then discard dogs? It certainly would not be for a normal pet owner. A significant part of ‘responsible ownership’ is that you don’t keep breeding or buying dogs and then dumping them once you can’t exploit them anymore – and yet this is basic operating procedure in greyhound racing.

This clause also makes the assumption that there is only one owner of the greyhound – what if the dog in question belongs to a syndicate made up of several people? Will every syndicate member all be expected to fund the ongoing costs for one nominated member retaining the dog as a pet after retirement, or will one member have to ‘buy out’ everyone else? If nobody is willing to care for the dog after he or she finishes racing, is this a ‘reasonable’ excuse to discard him or her?

Then there is clause (1)(a)(ii): “a person has contacted the GRNSW Greyhounds As Pets program and at least two other rehoming providers who have declined to accept the greyhound for rehoming”. This clause alone completely negates the purpose of LR106A: most rescue groups cannot take a greyhound immediately as they have an existing backlog of surrendered dogs and require the owner or trainer to put the dog on a waitlist until a foster home becomes available. Have a look at this quote from GAP’s website:

“We always have more greyhounds available to us than foster homes or permanent homes. We can only take a limited number of dogs into foster care at any one time and are unable to take dogs in at short notice.

“Because of the unavoidable time delay, we encourage owners/trainers to put their greyhound onto the waiting list well before the dog retires from the track. It is generally a good idea to place your dog onto the waitlist at least six months before your dog finishes racing.”

Dogs will still be euthanised because industry participants need to move them on to ‘make room’ for new greyhounds and cannot or will not wait for space to become available in these groups. There is nothing in LR106A that requires industry participants to continue caring for their dogs while they are on a rehoming group’s waitlist, so anyone who is asked to wait by two organisations and GAP can claim that the dog was not accepted for rehoming and therefore euthanasia is ‘necessary’.

Greyhound Racing Relies On the Public to Clean Up Its Mess.

LR106A does not address the real problem causing the euthanasia of healthy greyhounds by the industry: too many dogs, and not enough homes. Every rehoming group that we have spoken to in the last few months reported that adoptions have slowed down since last year – this has created a bottleneck as many dogs are stuck in foster care and groups are turning new dogs away because they have nowhere to place them. One rescue group director said, “If I said yes to every phone call I got, I would be taking in 30 – 50 dogs a week.”

It is unrealistic to expect members of the public to take in every failed or retired racing greyhound from the industry. Greyhounds are bred in the thousands annually in NSW – they are rehomed in the hundreds only. The pool of adopters is finite and limited, which many racing regulators’ welfare schemes (“let’s just increase adoptions every year, she’ll be right”) do not take into account. The reasons for this are numerous and usually out of the control of the industry and rescue groups, such as:

- Not all households are able to adopt due to their living situation or financial means.

- Some people prefer buying a pedigree puppy direct from the breeder instead of adopting.

- Some of the people who are willing to adopt instead of buy prefer other breeds to greyhounds and will continue adopting their preferred breed only.

- Adult and senior dogs are less popular for adoption compared to puppies, so retired greyhounds start off on the back foot purely due to the age at which most of them are discarded.

- Dogs with medical conditions such as broken bones that could turn arthritic or bad teeth that require expensive dental treatment are less popular for adoption compared to healthy ones with no existing issues.

- Keeping a dog is a commitment of roughly 10 years; once a household has adopted the maximum number of dogs it can sustain, it will not be able to take in any more pets for several years until one or more of their dogs pass away.

The greyhound racing industry needs to stop behaving like it is entitled to donations and free labour from members of the public to meet its animal welfare commitments. The only way to eradicate unnecessary euthanasia entirely is to reduce the number of greyhounds bred to match their demand as pets – otherwise, there will always be more dogs than homes.

The only thing LR106A will really do is to place the blame for a dog’s demise squarely on the shoulders of rehoming volunteers while industry participants continue to wash their hands of the issue they cause. It will place even more pressure on already-stressed groups to take every dog pushed at them, because they know that if another group says ‘no’ then the dog in question can be killed by his or her owner with no repercussions.

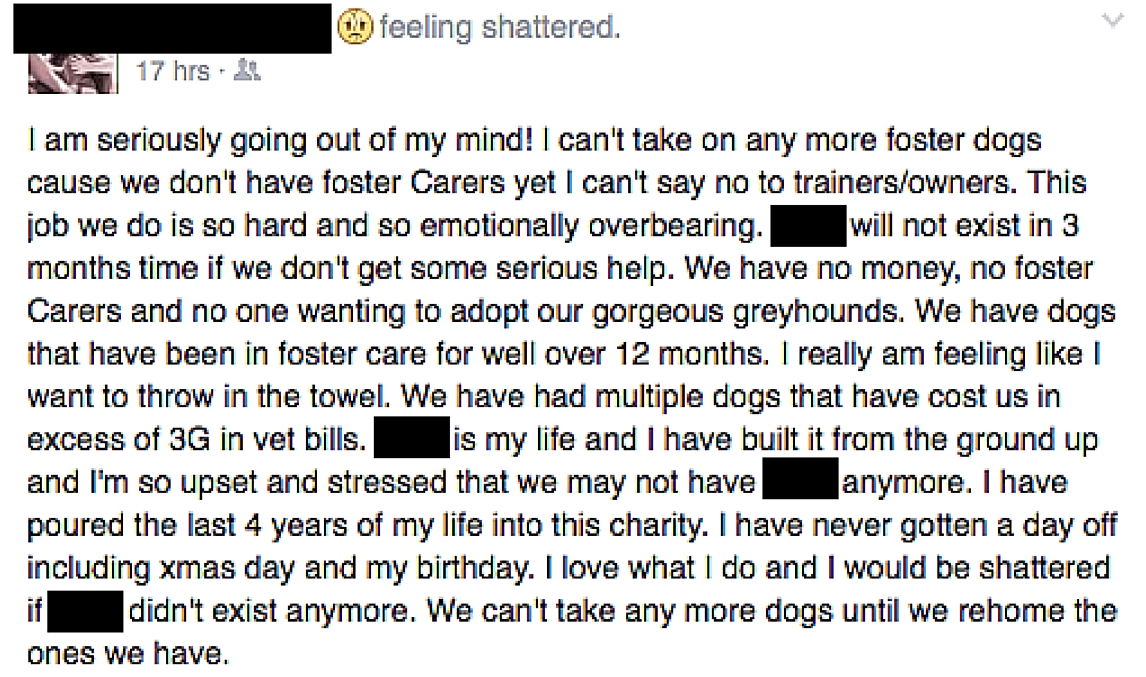

Many of the people who run or volunteer for independent rescue groups put in money from their own salaries to fund rehoming efforts – one of the rescue group directors we spoke to has spent around $50,000 of her own money to keep the charity going. Is it really OK for owners, breeders and trainers to exploit these dogs for their own financial gain while kind-hearted Australians give away their own hard-earned money to save them from death? And this isn’t even considering the mental and emotional toll that greyhound rescue takes on rescue group volunteers:

Rescuing greyhounds is an expensive exercise, as it incurs significant costs for transport, kennelling, vet work, food, bedding, coats, etc. Vet work in particular is a serious issue: desexing alone costs $200 – $300, and the cost goes up to thousands of dollars if the greyhound concerned has an illness or injury. Here are some recent examples:

- Gumtree Greys had to raise $2,800 for the emergency surgery of a race dog who was surrendered with a broken leg.

- Friends of the Hound had to raise $3,000 for surgery to fix a surrendered greyhound’s untreated broken leg. They are currently fundraising $6,500 to cover the vet bills of a 10-year-old brood mama who had suspicious lumps and dental issues, and a 2-year-old male who developed post-surgery complications.

- Amazing Greys had to raise $3,800 for an operation to repair an ex-racing dog’s untreated broken wrist.

- Nora’s Foster Hounds had to raise $1,853 for a 12-week-old puppy surrendered with a well-established hock deformity.

- Greyhounds New Beginnings had to raise over $3,000 for a seven-month-old greyhound puppy whose leg was so badly damaged it had to be amputated. This charity is currently attempting to fundraise $1,500 for a CT scan to diagnose the cause of seizures in one of their foster greyhounds.

Who wants to guess how much the greyhound racing industry contributed to these dogs’ vet bills? That’s right. Nothing.

LR106A does not compel industry participants to contribute financially to their surrendered dogs’ rehabilitation and healthcare – the money has to come from donations and fundraisers. Implementing this rule will increase the burden on rehoming groups, while participants get away with doing exactly as little as they were doing before for the dogs. GRNSW must understand that the industry cannot claim it has welfare at its heart, while expecting members of the public to foot the bill to rehome its dogs.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zgHrwhvzzUw]

A Question of Suitability

Another section of LR106A that is cause for concern is clause (1)(a)(iii): “a veterinary surgeon or rehoming provider has assessed the greyhound as not suitable for rehoming”. The lack of specific, measurable standards for this renders it vulnerable to misinterpretation and you’ve probably already thought of a few objections to this clause: Who is qualified to assess a greyhound as ‘unsuitable’? Who is qualified to determine whether a person is qualified to carry out an assessment? Who is going to set the standards against which a greyhound is measured for suitability or unsuitability? Who will come up with a repeatable, consistent method to test these dogs? How long after they retire from racing will it be before they are assessed? Will industry participants be required to take retired dogs home for a certain time period so they can learn about pet life before assessment, or will they be sent for assessment straight out of the kennels?

However, this is a mere distraction from the real question: “What GRNSW is doing to help create greyhounds that are suitable for rehoming in the first place?” This has a direct and obvious impact on the effectiveness of LR106A.

Greyhound racing currently sets these dogs up to fail as pets: the lack of training and socialisation in their early formative months, as well as the frequent moves from breeder to breaker to various trainers throughout their racing lives, can result in anxious, stressed and/or fearful dogs with complex behavioural issues. The training for racing is also at odds with what is desirable in a pet dog: greyhounds are encouraged from the start to chase and catch the furry, squeaking object, and yet they will suddenly be expected to ignore small running animals like white fluffies at the dog park or cats wandering the street after they are adopted.

This is one of the many welfare issues that was raised in the NSW Special Commission of Inquiry, and one that GRNSW’s proposed LR106A fails to address.

“…after their rearing part of the life cycle they go on to breaking education and training, and here they are exposed to a large number of potentially fear-inducing experiences. So they are transported often to novel locations, they are often put into a kennel for the first time, there’s new people involved, and these dogs haven’t been prepared for that, which causes a lot of stress, compromise welfare and contributes to wastage.

“…by the age of 12 to 18 months we have a whole population of dogs that have not been adequately socialised or exposed to normal stimuli, a whole range of things that we would expect our clients to do with their pets and things like that, to help their dogs to grow up to fully functioning adults in society. And these are all of the things that greyhounds may not be exposed to when they’re racing but certainly will be expected to cope with in retirement as well, which is a concern.”

This causes a bottleneck in the rehoming side of things as some surrendered greyhounds require a lengthy stay in foster care for rehabilitation and retraining. Some groups have reported dogs that need up to 12 months in foster care before they can be rehomed, which incurs a high cost and prevents them from taking in other hounds. It also restricts the already-limited pool of adopters to people who are experienced in dog behaviour and able (and willing) to care for dogs with special needs.

Tackle the Cause, Not the Symptom

Rather than messing these beautiful dogs about from birth to retirement and then expecting rehoming volunteers to ‘fix’ them during the foster care period, how about nipping this issue in the bud?

Instead of just relying on LR106A, GRNSW should make it mandatory for industry owners, breeders and trainers to provide every greyhound in their care with adequate, regular and ongoing dog training and socialisation (comparable to what pet owners are encouraged to do, e.g. puppy school, exposure to new environments, meeting other kinds of companion animals) up until the point where they are surrendered for rehoming. Help these dogs improve their chances at finding a home after retirement right from puppyhood, rather than neglecting all these crucial aspects of development and then expecting a couple of weeks in foster care to magically fix everything. At the moment rescue groups are still receiving greyhounds who do not know how to use stairs, which automatically cancels out every foster carer or potential adopter who does not live in a single-storey house. Is this really fair to the dogs?

Any industry participant who claims that they don’t have the time, money or ability to do this for every dog in their care should quit racing and find a new job that they are actually capable of doing right. And if many industry participants make this claim? Then it’s time to shut greyhound racing down, because that only proves that greyhound racing and greyhound welfare cannot coexist.

It’s time the industry took responsibility for the greyhounds instead of pretending they are someone else’s problem. Proposed LR106A, while possibly well-meaning, is fundamentally flawed and needs to be further defined and supported by other changes to achieve its aim of reducing unnecessary euthanasia.

The above is based on the Coalition for the Protection of Greyhounds’ submission to GRNSW’s request for feedback on proposed LR106A.